Today, for the first time, I saw this Sesame Street clip in which the human cast explains to Big Bird that Mr. Hooper has died, and won’t be coming back. If you grew up on early Sesame Street, like I did, you may want to brace yourself for the footage’s emotional impact. A transcript is also available if you can’t view the video, or can’t bring yourself to watch it.

Today, for the first time, I saw this Sesame Street clip in which the human cast explains to Big Bird that Mr. Hooper has died, and won’t be coming back. If you grew up on early Sesame Street, like I did, you may want to brace yourself for the footage’s emotional impact. A transcript is also available if you can’t view the video, or can’t bring yourself to watch it.

My long-time readers know that I’m a major proponent of the pedagogy behind and execution of the early works of the Children’s Television Sesame Workshop, and that one of my side projects helped push them into releasing some of the old content onto DVD. So why is this the first time that I’ve seen this clip? The truth is, when this first aired, I wasn’t allowed to watch it.

I guess it’s time I opened up a little bit; I haven’t really felt like bearing my soul online for a while, and this feels like the right opportunity. (If this degrades into solipsistic, indulgent self-pity, please tell me!) In 1981, at the end of grade 3, my parents packed us up and moved us from New Orleans to Chicago. The move was traumatic for me in a lot of ways. I’d never lived anywhere north of the Mason-Dixon line before. My body didn’t cope with the cold very well. (It still doesn’t!) We went from living in a semi-detached house with a backyard and swing set to a tiny apartment in a poorly-maintained building in Streeterville, long before it was a trendy place to live. I shared a room with my brother, barely big enough for two beds, a dresser and a child’s desk. Camaraderie was radically different, and I struggled to fit in. My new classmates ruthlessly made fun of me when I used words like “y’all” or “la-bas.”

I also left behind friends in New Orleans. Most importantly, I left behind my paternal grandparents, who’d shared the responsibility of raising me since birth. There was a distinct cultural difference between the way my parents and my grandparents ran their households. My grandmother would encourage me to understand and work through my feelings, and my grandfather generally stayed out of her way while she guided me through them. (Never mind that they fought daily. It seemed to work for them.) On the other end of the spectrum, my parents were mostly intolerant of my frequent emotional outbursts. More often than not I was sent to my room or physically disciplined when I cried. They seemed to be trying to convince me to make Mr. Spock my role model.

Probably the hardest thing about the move was school. Down south, I had skipped two full grades, with the full support of the school, my guardians and my classmates. Up north, I was told that no public school would take me into grade 4, and my parents couldn’t afford any private schools that would. So I was forced to repeat grade 3 in a public school whose curriculum was closer to that of my previous school’s grade 2. I felt an overwhelming amount of anger and frustration over this. The worst of it was that mother didn’t finesse the situation very well: she told me it was my fault that I wasn’t emotionally mature enough to be accepted into a private school, or grade 4, filling me daily with huge amounts of guilt and shame. This was used as the trump card whenever she felt I was being “too emotional” – shut up, don’t cry, remember: that’s why you had to be held back a grade.

So I should have seen it coming: when I was accepted into a private school for grade 4, there was a simultaneous parental ban on anything that was “too childish” for me. My toy chest, lovingly hand-built by my father, and all of its contents were given to my brother. I fought with my emotions as I watched my father paint white over my stenciled name, then paint my brother’s there instead. My piano studies moved from light-hearted instructional books aimed at children to more serious classical works (Bach two-part inventions, Mozart, etc.) Oh – and there was a complete ban on all childrens’ television (and most network programming as well.) Sure, I managed to sneak in watching some over my younger brother’s shoulder from time to time, but when caught there was violent reprisal.

When Will Lee (Mr. Hooper) died in December 1982, I heard about it from my classmates. I couldn’t believe it. I’m pretty sure a bunch of us cried about it, though at a private school one doesn’t show such emotions publicly. (I spent a lot of time in the bathroom trying to work through my emotions, I remember.) As my mother picked me up from school, I badgered her about it. She confirmed she’d read about it in the morning’s Chicago Tribune. Back then CTW hadn’t decided what they’d do about the death yet, and the papers were full of speculation. In August 1983, they announced that they’d have Mr. Hooper’s character die on the programme. I remember asking to watch, even trying to watch when it aired, and not being allowed. Even then, I didn’t understand why not. Did my parents not want me to learn about death? Did they want to own that part of my development? Or was it simply a belligerent stand against “childish” influences in my life? Gradually, the whole thing washed over, and everyone moved on.

That is, I moved on until today, when I finally watched the clip from my office at OISE/UT. It’s a good thing no one else was here when I started to cry! And then, just an instant later, there was this very loud introject telling me not to cry, not to show emotion, and even reminding me that this is forbidden material that I should switch off. I struggled with myself for a few seconds, until I told myself: “You know what? It’s your turn to shut up. This is important to me. Maybe not forever, but right now I need to experience this and deal with my emotions. I can’t wait any longer.”

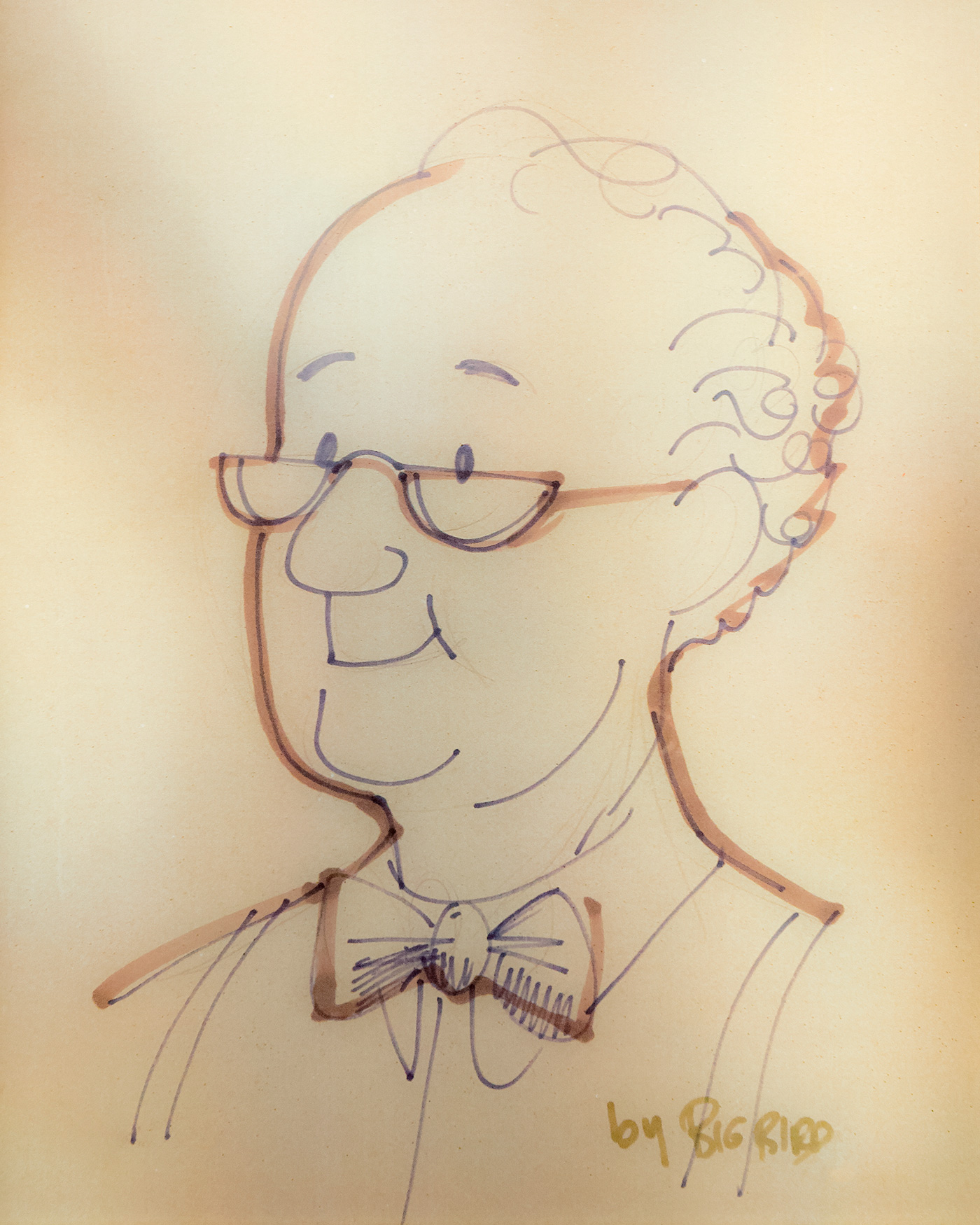

The whole clip felt like a Greek tragedy: the dramatic irony in Big Bird’s slow realization that Mr. Hooper wasn’t coming back, long after I’d learned it and processed it, didn’t stop me from a huge outpouring of emotion. I felt the awkward moment of silence just after Big Bird says “I can’t wait until he sees [the drawing I made of him]” both as an adult (“How do we deal with this situation?”) and as a child (“Where did he go?”) Then I put myself inside each of the cast members as they spoke, trying on each of their different ways of dealing with and expressing grief: Maria’s unflinching honesty, Susan’s calm explanation paired with a gentle touch on the arm, Luis’ detached explanation of the facts, David’s quavering description of the future (and how inheritance works), Bob’s (oh Bob! I miss you!) commiseration and brief eulogy, Olivia’s strong affirmation of life after death through memory, and, ultimately, Gordon’s explanation – the only one that made sense to Big Bird, and perhaps ultimately the only explanation: “just because.”

Writing this post was the dénouement to a catharsis 25 years in the making, almost to the day. I’m glad I finally watched the clip, finally felt my way through the loss of a fictional childhood friend, and didn’t have to repress my emotions or pretend they didn’t exist. And – I’m glad I shared it all with you readers in cyberspace.

Wow, that’s one of the heaviest Sesame Street clips I’ve ever seen. I hadn’t seen that one before. I got a little teary eyed too!

Thanks for sharing. I remember seeing this as a kid (must have been in repeats). I loved Sesame Street so much. I remember being 10 or so, and feeling embarrassed to ask my mom to buy me a Sesame Street magazine because I didn’t want to seem babyish….

Thanks for posting, I’d read about it (and read the storybook scans) but never seen the clip. I remember Mr. Hooper (being 8 when he died), but never saw this one. *hugs* -j